- Home

- Stuart Rojstaczer

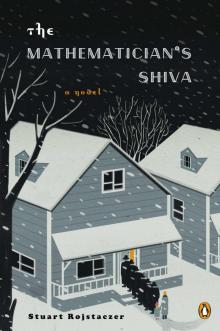

The Mathematician’s Shiva Page 7

The Mathematician’s Shiva Read online

Page 7

These events would repeat themselves at almost every concert we attended. Even as a child, I couldn’t understand why the KGB didn’t have a picture of my mother, so that they could intercept her before she made their work so difficult. The look of satisfaction on my mother’s face as we walked back to our seats would be absolute.

But every once in a while the script would change. The blue suits would be doing lord knows what. They wouldn’t be paying attention as my mother beckoned an artist to defect. Even rarer still, the performer’s eyes would lock into my mother’s stare as if hypnotized, as if this were a dream come true. A woman was telling him in perfect Russian what he had been thinking for years, reading his mind. At such times my mother would pass a piece of paper into the hand of the artist quickly, with a nod. “You call,” she would say. “You call me whenever and wherever. I will take care of you. I will make sure you are safe.”

As a child, these “successful” exchanges filled me with pure panic. They were far worse than the embarrassment of being whisked away by the KGB. What if a call from one of these adult urchins did come? What trouble would my mother, so fervent in her anticommunism, get us into? The frequent intrusions of mathematicians visiting our house and sleeping on our living room couch or, worse yet, taking over my bed and making me sleep on the couch, were bad enough. I thought ahead and had visions of being exiled to our living room couch for years, usurped by a new needy member of our “family.”

My mother was bound to succeed sooner or later. Two years after she handed a ballerina a slip of paper with the alphanumeric string HI4-6572, the HI standing for Hilltop, it happened. I, at the tender age of thirteen, picked up the phone and heard the panicky voice of Anna Laknova, who, like my mother and Kolmogorov, was brought up from the dust and, through the Soviet system, polished into a shining jewel of talent. Disappointed to hear someone who obviously was not an adult, Anna demanded to speak to my mother.

“She is at her office at the university,” I said, thinking I was talking to yet another Russian mathematician.

“Ay, ay, ay, she said she would be here. She would take care of me.” And I knew instantly what this was about.

“You are in what city? Chicago?”

“Yes.”

“Where?” I could sense she was worried about giving this information. “I’m the boy who was with my mother and father backstage,” I tried to explain. “I will go to my mother’s office. We will drive to meet you. But you need to tell me where.”

My uncle drove the first new car he ever owned, a Chevy Impala. My mother rode shotgun, and I sat in the back of the car reading Gogol or some other Russian writer. In our home, reading was more important than conversation. When there were no guests at night, sometimes the only noises you could hear were the creaking of chairs, the sipping of tea, and the almost silent sound of pages being turned.

I was having a hard time concentrating, though. I was giddy. I might have to live on the living room couch for the rest of my years at home, but this was something far better than watching a TV spy thriller like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. We were a part of a real piece of Iron Curtain intrigue. Plus I could tell that my mother was so proud of me for keeping my wits and writing down everything we needed for this freedom mission: the name of the woman, the exact address where she was hiding, and the precise meeting time.

But the truth was that—like most events that sound so exciting on paper—picking up this ballerina was a mundane thing. We parked our car along an elm-lined street of three-story brick apartment buildings, were buzzed into one of them, a door was opened, and there she was, a frightened woman perhaps twenty-one years old in the apartment of a Polish hotel maid.

OK, it was not entirely mundane. This ballerina was, to a thirteen-year-old boy, the quintessence of beauty, lean and graceful, delicately featured, exuding natural elegance, her long dark hair in a bun. We took her to an FBI office in Chicago, where she formally defected, and we filled out what seemed like a ream’s worth of papers attesting to our willingness—without any promise of help or aid on the part of the U.S. government—to house and protect this defector from harm until she would be formally accepted as a legal resident of the United States.

They would become a formidable pair, my mother and Anna. Physically, they were so different. My mother towered over her dark-haired, olive-skinned, diminutive ward. In other ways, too, they contrasted. My mother had her overpowering intellect. Anna, so self-possessed that she scared all but the most confident and foolish of men, had her physicality. Perhaps you could count me as one of the foolish ones. Unlike any of the others, she would never toss me aside when she grew bored. I was as close to a brother as she would have. Tell me, what man doesn’t want a self-assured, beautiful sister who men look upon with desire? You are the one man with whom she shares her secrets. You are the one who has a piece of her heart forever.

Anna’s defection was a two-inch story in major newspapers across the country. It was something buried on page fourteen, next to ads for things like Pall Mall cigarettes. Who cares about ballerinas, even world-class ones, in this oh-so-practical country?

Anna would go on to perform in New York for many years, and then move to Los Angeles to marry a movie director. This marriage—one of three total—would last for six years. She taught dance, and even worked with my cousin for a time, helping out with choreography for his TV specials. She would usually come to Madison once a year to spend time with the family that had generously given her a new home. After my mother was diagnosed, Anna started calling her once or twice a week and flying in on occasional weekends.

When I got a call on my cell, I heard the sadness in her voice, the same sadness I felt. “Is Bruce with you?” I asked.

“He’ll be here later tonight,” Anna said.

“It’s good. I need you both here. It would be too hard without you,” I said, lapsing into Russian, something I rarely do on my own.

CHAPTER 9

In My Room

When a family sits shiva, you have to do some rudimentary things to prepare the house. You cover mirrors, so as not to look at your dreadful personage. You cover photos, too. Why should anyone be reminded of any events of the past? You do that enough in your head without visual cues. I think this rule should apply more widely. Add bookcases to the list. Why would I want to be reminded of the books I read as a child in my mother’s house?

I took over my old room, mercifully absent of anything from my childhood. There was a picture of my mother and my grandfather on a desk. That was it for memories. Those two were now gone. How many people were left who remembered them together? Me and maybe a dozen others. In another thirty years, the number would be zero.

I dragged an air mattress up the stairs that Uncle Shlomo managed to borrow from someone, blew it up, and put it dead center in the room. A week here would be fine, I thought, as I looked out through the lace curtains to the icy backyard and the park beyond. Bruce took over my mother’s bedroom. Anna was supposed to be in there, but Bruce protested that he was not going to sleep in the sunroom because it housed a “dead person’s bed.”

“My mother died in the hospital, not here,” I said.

“It’s a sickbed. What’s the difference?”

“You can’t contract cancer from a bed, Bruce.”

“You a physician all of a sudden?”

Bruce was by far the most American of us, the only one who had actually been born in this cherished land. In the world of Los Angeles, no one would guess that he was related to people like us. His cultural divorce—ultimately superficial—took place when he went to college. When he came back home from Williams his first year, he talked like a Boston Brahmin. After his junior year in Italy, he took on an Italian accent that he kept well into his mid-twenties. But in Madison, he tended to regress. This town was not good for him. I knew this. Even his father knew this. When Shlomo, with whom Bruce had long reconciled after some

very tempestuous teen years, invited him to stay at his house—a faux-palatial estate with Ionic columns, marble floors, and a couple of gilt statues of Roman women in various classical poses—he knew what the answer would be. Anna, however, was far less patient. “You’re being a big baby,” she said, and reluctantly swapped rooms with Bruce.

My room had once been my haven. I would come home from Chicago—where I was living my ironic life of religious instruction mixed with a nascent atheism and a lust for the daughter of a delightful and naïve couple—and spend hours in my room alone. I’d read novels and philosophy and write thoughts that at the time seemed profound. When I read these heartfelt musings now they seem ridiculously morose and infantile.

No one seemed to be worried about—or maybe no one noticed—my descent into teenage narcissism except my grandfather, for whom we had made an expansive room out of the attic. Grandpa Aaron was a pragmatic man. He was not a poker player, a bridge player, or a chess player. He liked to read the news. He read Barron’s from cover to cover. In a home full of distracted people, he made up for us all. He was our chief financial officer and invested my parents’ money well. My grandfather opened the door of my room one day without knocking—privacy was nothing my family believed in—and maybe if I had been reading Gorki or Flaubert or Turgenev, he would have just shrugged. But he saw the name on the cover of the book hiding my face and erupted.

“Kafka! What goddamn sixteen-year-old boy reads Kafka? Out!”

“What do you mean?”

“Out! Out of this house! Do something! Play some stupid game, baseball or something. Go shtup a girl. Don’t read this dreck!” He reached over and grabbed the book from my hands. “Kafka was a mamzer.”

“What do you mean? How can you say that? It’s not like you knew him, zaydeh.”

“Get the hell out, I tell you. Look at this stupid writing,” he said, thumbing through the pages, then resting on one. “‘K. looked at the judge’ . . . yob tvoiu mat. That idiot sat in his apartment all day making up dreck like this. Depressing stuff. You want to be an idiot like him?”

I looked at my grandfather. He wasn’t talking abstractly or making assumptions. That wasn’t his style. “You really knew him, didn’t you?” I was getting excited.

“Kafka was Czech. I’m Polish. Why would I know him? I heard of him, certainly. I knew of him. I forced myself to read his dreck a long time ago.”

“He was a genius, zaydeh.”

“Genius? What the hell are you talking about? Your mother, that’s genius. Kafka? A scribbler for the depressed, lost, and spoiled. Worthless dreck.”

“So why did you read him?”

“Out! You get the hell out of here. You writing depressing shit like this, too?”

“I’m trying, yeah.”

“No. Not in this family. I will not have a Kafka in my family. Out!” My grandfather ripped the cover from the binding of The Trial and threw it into the hallway. “That man caused enough trouble when he was alive. Screwed up a girl from my hometown.”

“But you said you didn’t know him.”

“No. I didn’t. But there was a girl from Komorow, a dorf not far from where I was born. She knew him. Screwed up her life forever.”

“She knew Kafka?”

“Yeah, she knew Kafka and I knew her. Beautiful girl. So intelligent. She could talk about anything in such a beautiful Polish. Broke her mother and father’s heart. She moved to goddamn Prague to take care of that sick mamzer.”

“She was a nurse?”

“A nurse? What kind of nitwit grandson do I have? A nurse. Yeah, right. Like Rebecca Weidman in Chicago. She a nurse to you?”

“She’s a friend.”

“A friend. A special kind of friend.” My grandfather was chuckling. “Pretty good deal you got down there. I got to hand it to you. You eat Mrs. Weidman’s shabbas meal, say a few prayers, and then, you little devil, what do you do? You didn’t get this from me or your mother, that’s for sure.”

“She’s just a friend is all, zaydeh. I don’t know where you get such ideas.”

“You’re worse than Kafka. Little liar to your zaydeh. Out!”

I never found out how my grandfather learned about Rebecca and me. But the network of Polish-Jewish émigrés in the Midwest was tight. Fortunately, Dr. Weidman and his wife were born in the United States, and both their parents were long deceased. If the grapevine hadn’t passed them by, I can well imagine what I would have had to endure.

At first, I didn’t believe my grandfather’s story about a girl he knew falling for Kafka, but it more or less checked out. Dora Diamant, daughter of a well-to-do devout family, was the girl in question. She managed to make it to England before the war. Perhaps there were only two degrees of separation between myself and my hero. But with my family, you never know. The details that define the stories of our lives are malleable. If it isn’t science or math, it’s fair game to be trampled upon, stretched, wrung out of its water, and rehydrated with vodka. My grandfather, like everyone in my family, was a skilled liar. Maybe my zaydeh had simply heard about this girl and appropriated the story in an effort, no matter how ineffectual and ridiculous on the surface, to teach me a life lesson.

He was in the living room when I decided to find out what was what.

“You knew Dora Diamant?”

“You still reading that little mamzer Kafka?” He put down his newspaper and took off his glasses.

“Yeah. He’s brilliant. Way ahead of his time.”

“So you say. Man wakes up as a cockroach. This is brilliant? A stupid joke, really. Dora Diamant? She could have had anything she wanted. She was beautiful, she was smart, from a good family. And what happened? She fell in love with a sick man who for amusement told stories about insects that people take seriously. The joke is on us.”

“Did you really know her?”

“Know? Idiot, I was supposed to be married to her, is the truth. My father and her father got together. I was eighteen. She was fourteen. It was planned in advance. Sixteen years old and she runs off to Prague to be with that little mamzer.”

“So you and Kafka were in a love triangle.”

“Love triangle. What kind of dreck are you telling me, Sashaleh? She was supposed to marry me. It had nothing to do with love. A triangle needs three vertices. There was no triangle.”

“So you had to find someone else?”

“No, my father had to find someone else. He found your grandmother. My father’s brother’s daughter.”

“You were cousins?”

“Yeah, cousins. Dora made a mess of the whole thing. My stock as a potential husband was down. My father did what he could to find a suitable match.”

“We’re like rednecks then, zaydeh.”

“What are you talking about? I was educated well. I know six languages. I manage the family investment portfolio. Your mother and father are both professors. Your mother is brilliant. We are not rednecks, anything but.”

“But you married a first cousin.”

“That was done in Poland. Royalty did such things, too. Dukes, duchesses, princes, princesses. It was a custom. We aren’t rednecks. We’re European. Big difference.”

“You ever meet her again? After the war?”

“You’ve got to be kidding. What would we talk about? It’s been fifty years. What did you find out about her, anyway? She ever marry and have children?”

“Never married. She had one child. Died in England, I think.”

“See. That mamzer screwed her up for life with his stupid stories. You writing stories about turning into a cockroach?”

“No. Different stuff.”

“A ladybug maybe? A tuna fish?”

“Zaydeh, don’t tease me. It’s hard to write. It’s hard to find the right words.”

“Good. You don’t have it in you, to tell you the truth. I

wrote some nonsense too when I was your age. You’ll get over it. You’ll be a mathematician or something. But a scribbler? You have an ayzene kepl, not something full of craziness.”

Maybe this is the kind of stuff you’d expect to think about when your mother has just died and you glance at a photo of your mother and grandfather that you have neglected to cover up for the shiva. I knew the photo on the desk in my old room was a reunion portrait taken in Forest Hills, Queens, in 1952. My grandfather’s war story differed from my mother’s once Stalin “liberated” all Polish citizens from the work camps in 1941. He was conscripted into the Russian army—leaving my mother with a refugee family also from Vladimir-Volynski—and sent to oversee missile production near Samarkand. When the war ended, he went west, back to Vladimir-Volynski briefly, and upon hearing the stories of the mass murder there, continued into Poland, certain that his son was dead and that the family that kept his daughter would travel to the West just like he was doing. After all, it was the most logical step. But he was mistaken in this assumption. It was one of the few times my grandfather ever made a truly bad guess. His daughter was in Moscow studying. The family that took care of her during the war, not nearly as resourceful as my grandfather, could not manage to cross the border into Poland and lived a precarious existence in Kiev.

My grandfather emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1949, two years before my mother defected. The presence of my grandfather in the West, something she discovered in 1948, made it somewhat less surprising that my mother defected and temporarily abandoned her husband and son. With my grandfather present, she would not be completely alone. The photo in my room was taken when my mother was twenty-two years old. She had not seen her father in more than ten years. They walked into a photo studio on Queens Boulevard, and my mother was not in braids as per usual, but instead was trying hard to look mature and stylish, with her hair held in a bun in back à la Grace Kelly. With money from the immigration charity HIAS and in anticipation of moving to Madison to take her American academic job, she had bought her first American outfit, an elegant summer dress with a little lace trim. My grandfather was in a wide-lapelled jacket and tie, his fedora at a tilt. Both of them looked damn good. America had agreed with them instantly. They were easily taking root, as would I, and as would my uncle and father. We were a naturally adaptable, if too small, family.

The Mathematician’s Shiva

The Mathematician’s Shiva