- Home

- Stuart Rojstaczer

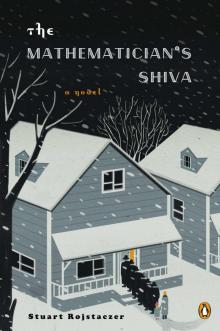

The Mathematician’s Shiva Page 3

The Mathematician’s Shiva Read online

Page 3

“Yes.” My father shows a glint of a smile. I can always recognize that look, the way his face stretches taut. This is my father when he is lost in the moment. He knows I’m on the right track now.

I take the pencil out of my mouth and draw a path. “That’s easy. I could do that, too. There are lots of ways.”

“You’re a clever boy,” my father says.

I’m pleased with myself. In hindsight, I usually view my childhood ego as some monstrous thing. I thought that not only would I achieve greatness, but that I fully deserved it. My grandfather Aaron—who lived in our home through my childhood and beyond—called me his ayzene kepl, his little iron head. When I first heard this phrase translated, I thought he was teasing and calling me stupid. But I was quickly reassured that this was a good thing. I had something substantial in there, the mind of someone older.

“Can we make bananas now?”

“One. Just one. Just like Leo.” That’s what we do. We walk to a store on Regent Street and buy one Cadbury chocolate bar, its gold foil signifying its luxury. Then we walk to Park Street to the closest grocery, and buy one banana. We stand in the kitchen, and my father tells me that chocolate must be steamed to be melted. I stand over the stove on a chair and watch the chocolate liquefy and spread in the stainless steel pan, glistening and sending forth wisps of vaporized oil as it melts. My father has no taste for chocolate. It’s my mother’s weakness, not his. He eats apples, sometimes whole onions, after he peels the outer skin into a thin spiral with a pocketknife. But this land of plenty we live in never ceases to give him pleasure. I can tell he’s enjoying this activity because he now has the ability, within reason, to buy anything he wants and can do something as whimsical as cover a banana in chocolate.

Years later, I’ll remember this day and realize that the Leo in this story is Leonhardt Euler. In truth he’s not a boy walking across bridges but a man, one of the finest mathematicians ever known. He will found a field of study in the eighteenth century, topology, which will consume the mental energy of many friends of my parents. And yes, it will also take up the mind of the great Kolmogorov for some years, a restless mind that will touch almost all of mathematics.

If you think it’s torture to put a kid through such an exercise, I vehemently disagree. My father is teaching me to be a mathematician, and like most any other skill or art—and mathematics is definitely an art—those who learn early have an innate advantage. The tennis players you watch at Wimbledon and the quarterbacks you see in the Super Bowl are never taught their craft for the first time in high school or college. Why should it be any different for mathematics?

Just so you know, my father was being easy on me. The problem Euler faced was actually ridiculously and hideously more difficult. Euler wanted to cross seven bridges, not six, in his hometown of Königsberg. The real answer to the actual problem—crossing seven bridges—is that it doesn’t have an answer. It is impossible to walk across seven bridges without using one of them twice. Euler proved this to be so. If my father had given me, at the age of six, this impossible problem, tried to get me to realize the problem was impossible, and prove it was so, now that would have been torture.

A proof. An ironclad irrefutable statement of what is or isn’t possible. For three centuries at least, mathematics has been all about that one thing, and every new proof is celebrated by the community. Even minor proofs get a few minutes of sunshine.

I’m not a mathematician. Despite my early training, I don’t have my parents’ talent. I am good. I am clever. I am certainly not brilliant. But like my parents, I have a love for the elegance of proofs, their absoluteness.

Over the course of my childhood I will be introduced not only to little Leo but to little Isaac (Newton), Blaise (Pascal), Pierre (de Fermat), René (Descartes), Gottfried (Leibniz), and many more, all of these mathematicians playing the role of resourceful and independent boys, and all giving me the idea that solving problems always came with tangible rewards. Ah, if only life were so simple. Then there were the men and women, real men and women of today, not imagined boys, who came to visit us, and they knew the names of these mathematicians as well. In contrast to my father’s fastidiousness, many seemed unable to even tie their shoes correctly.

When my father warned of the horde of mathematicians that would descend upon our house after my mother’s death, I knew what to expect. They would be grieving, but not like my family. They would be mourning not my mother but the loss of ideas, the loss of intellect. They would no longer be able to sit in a room with her and feel the magical presence of someone with the talent to find the hidden gem in what is thought to be all dross.

The Hasidic Jews have a word, dveykus, for men who always possess the spirit of God inside them. My mother, unlike my grandfather, did not believe in such things literally, but when it came to understanding mathematics, she knew that she possessed the equivalent of dveykus. Like a rebbe with acolytes who feel blessed just to be around someone whose goodness and spirituality are always present, my mother had her followers. I had been with them all of my childhood. They sought me out for my secondhand dveykus even as an adult. Now they would come and I would have to be their gracious host for seven days, the days of shiva that are a traditional part of Jewish mourning. My uncle called them the szalency, the crazy people. Yet he would supply the vodka, and soothe them in his own way.

But I am getting ahead of myself. In this story, my mother isn’t even dead yet, and already I’m talking about her shiva. We need to go back to the hospital.

CHAPTER 3

Without Yozl Pandrik

The cross over my mother’s bed, it turned out, was not hard to remove. Father Rudnicki came back with a screwdriver surprisingly quickly, handed it to me, and stepped out for a few minutes as I pried Jesus easily from the drywall. He left barely a mark on the glossy pale paint.

“Give him to me,” my uncle, who had returned with two fresh bottles of vodka, said. Unlike my mother, my uncle had not lived above the Arctic Circle during the war. Instead, he ended up housed in a convent in the Polish city of Tomaszów-Lubelski. My uncle delicately fingered the crucifix in his hands. “They are giving Jesus six-pack abs nowadays,” he said. “In Poland, he was a skinny little thing. Here he looks like he has been pumping iron with what’s his name.”

“Schwarzenegger?” I asked.

“Yes, that’s the one.”

My uncle walked up to Father Rudnicki when he came back, his instinctive childhood deference to all men and women who served the faith fully intact. “I do apologize for my sister, Father. She is not always respectful of others. But she does have a good heart.”

“I know she does, Mr. Czerneski.” They continued their conversation in Polish and, of course, along the way my uncle managed to pull another urine cup from a drawer and offer Father Rudnicki a well-earned drink. My uncle has no mathematical skills whatsoever, but he does know many languages. Polish, Russian, German, Hungarian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and even a language that seems to be one long whisper to me, Lithuanian. Though he came to the United States at the age of twenty, his English is without even a trace of an accent, except when he is drunk or tired.

My uncle had come to the United States in 1957, traveling from Warsaw to Chicago with a vague notion that he had relatives somewhere in this too large country. He knew, although he never practiced the religion, that he was Jewish, which is why the Polish government had let him travel in the first place. Back then they were always eager to remove whatever physical reminders—people, buildings, and even tombstones—remained of their once bountiful Jewish past.

His plan was simple. Go to the cities with the biggest Polish populations and search for his family. What better place to start than Chicago? But there were no Czerneskis in the Chicago phone book, and no synagogue had any recollection of anyone by that name. He found a job mopping the floor and washing glasses at a rickety bar owned by a childless couple born near his hometown. On a win

ter day, a Polish mathematician visiting Chicago walked inside. He and my uncle struck up a conversation. When my uncle mentioned his name, the mathematician remembered the papers of Rachela Karnokovitch from her unmarried days.

“It’s a name well-known in mathematics, Czerneski. There’s a paper by Kolmogorov and Czerneski. A classic in its field. Perhaps you are related.”

“Could be. Is he living?”

“It’s a she, not a he. She’s in Wisconsin now.”

I have actually met this mathematician and that was the story he told me about the first time he encountered my uncle. My uncle’s version is a bit different, less matter-of-fact. In my uncle’s version, he goes to the Chicago city library researching anything about anyone with the name of Czerneski. In a Russian book he finds a reference to a mathematician, R. P. Czerneski, student of Kolmogorov. He finds this “classic paper” written in German for the periodical Mathematische Zeitschrift. He cannot, of course, understand its contents, but somehow my uncle feels that this paper is significant to him. He cuts it out with a razor blade and carries it in his coat pocket for days. Then the Polish mathematician shows up in the bar. He shows the man the article and is told that the author, a woman, lives in the United States.

Whose story is correct? It doesn’t really matter, does it? Now the stories converge, more or less. My uncle hears the woman’s first name, Rachela, and though he cannot remember anything at all from his days as a young boy in Vladimir-Volynski, this name conjures forth an image of a girl with pale skin and the lightest of hair, holding him. He’s seen this image before in his mind and in his dreams. Until now, he thought it was an angel holding him as a young boy, comforting him, protecting him. He always imagined that this angel had wings. But in the bar, when he hears the name Rachela, the image appears again and the wings are not there. It’s not an angel that is holding him. This is how memory works, I know, full of clichés precisely because the pictures we hold in our minds are usually the most trite.

“You’ve met this Rachela?” my uncle asked the professor.

“Yes. She is without peer. Born in Poland. Educated in Moscow.”

“Born in Vladimir-Volynski, yes? Jewish, but with the face of a Pole, broad, not like mine.”

“How do you know this?”

“That woman is my sister.” As my uncle said this he reached out and hugged the mathematician. I know this bone-crushing hug, its ability to force every molecule of oxygen out of your lungs and make you understand that true vitality requires some awareness that life is both fragile and temporary. My uncle is binary. He is either at rest or fully alive.

Now I am not trying to pull your heartstrings with this tale of long-lost siblings finding each other. It is not my style to dwell on the sentimental, but neither can I avoid it. I am stone-cold sober as I write this part of my story, although I do admittedly drink too much sometimes. My uncle is an emotional man through and through. With my parents, I can, if I wish, be distracted from their tumult and raw nerves by their work, so elegant, pure, and beautiful. But there is no other side to my uncle. Just thinking of him immediately makes me think of his rough beard scratching against my cheeks as he holds me and kisses one side, then the other. Through all of his years, he has attracted women who would, if asked, do anything in their power to come to his aid. I know exactly why. Who can resist such a life force?

After the mathematician left the bar, my uncle called the home of Rachela Karnokovitch in Madison, Wisconsin. His English was still rudimentary, so he began in Polish. He introduced himself and told my mother where he was born. You’d think my mother would have been surprised by this call. What were the odds of such a thing happening? But no. This most logical of women was always sure, somehow, that her brother survived. Every Yom Kippur she would light a yahrtzeit [memorial day] candle for her mother. But she was convinced her brother, little Shlomo, still lived. When she prayed it wasn’t for his life. It was for the hope that one day she would see him again.

The conversation fell into the familiar almost immediately as my uncle heard that perfect accent of eastern Poland. His money was running out—this was back in the days of AT&T’s monopoly, when phone calls even over distances of 120 miles could quickly eat at daily wages—and he told his sister to call him back. He waited for what seemed like a ridiculous amount of time in the frigid Chicago telephone booth, the vapor from his lungs forming clouds, and when the phone rang, he brought the receiver to his ears, longing to hear that voice again. My mother told him the story of his childhood, of the planes flying overhead in 1939 and how their mother, literally hedging her bets and not believing her little boy had the strength to travel to the unknown in Russia, left him behind with her sister in Vladimir-Volynski.

My uncle was two years old at the time. And the only real memory he had of his days in Vladimir-Volynski started to make sense as he heard this story. Images will come to him over the next year. His earliest memory is from 1941. A dark-haired woman is holding him against her breast on a clear day in an open, grass-covered field. There is the sound of gunfire and the woman falls. He clings to her body even as she falls into a pit, and pretends to sleep, hoping that perhaps if he simply closes his eyes he can will this moment away. He remembers the musty smell of the dirt covering him, and the stillness all around him as he gasps for air and starts to claw at the dirt above, trying to find light.

This is my uncle’s will at work even at the age of four. He will somehow manage to dig himself out of the ground by his small fingers, pruney, no doubt, from the moisture in the soil, and find the air to breathe. He will run from this killing field—today covered in chest-high grass in the summers and marked with a single concrete memorial pillar, Soviet in its pragmatism and with a few misspellings—into the surrounding forest and survive by himself for he doesn’t know how many days. A Polish family will find him as they flee, not from the Germans, but rather from Ukrainian fascists practicing their own brand of ethnic cleansing.

In the hospital, my uncle told the priest a short version of this story. He ended it with a sentiment that I’d heard many times from him. “I’ve already been dead and buried. There is nothing anyone can do that can possibly shock me.” But in my mother’s hospital room, my uncle was undeniably fearful, and he was talking at a fast clip.

“Have you been to Poland, Father Rudnicki?” my uncle asked.

“No. I’ve never found the opportunity.”

“I should take you. I haven’t been in so long. Sasha as well. Maybe even Viktor. My son Bruce. It would be a good idea. Rachela would like it. All of us together.”

“I would, to tell you the truth,” my mother said.

“I barely speak a word of Polish, Shlomo,” my father said. “I’m over seventy years old. You want to drag me back to a place where you can still smell horseshit in the streets?”

“It wouldn’t be so bad,” my mother said. “You’d be a tourist, not a citizen. If Cynthia came with you. Now that would be funny. That I would like to see. I wish I could watch from above. The lalka in her high heels trying so artfully to avoid the piles on the cobbles.”

“Cynthia in Poland,” my uncle said. “That is funny.”

“You should take her,” my mother said.

“No. It’s a man’s thing, this trip. But you could go with us, for sure. If I tell you we’ll all go tomorrow, will you let them fill you back up with blood?”

“It’s not that simple, Shlomo. No. I’m done. This is a good way to go, actually. I have people I love around me. The morphine makes me feel dreamy. Sashaleh, what do the pressure numbers say?”

“They keep dropping.”

“I know. You keep looking at them. You think they are going to go higher by some miracle?”

“I can always hope, Mother.”

“You’ve been a good son, the numbers can drop. It’s OK.” She looked at the rings on her fingers. “Shlomo, you can take off the jewelry no

w.”

My uncle rose out of his chair and kissed his sister on the forehead. My mother loved jewelry. The thicker the gold and the bigger the gem, the better she liked it. It wasn’t so much about display. “Even in this country, you never know,” she said. “You might need to leave in a hurry. Gold is always valuable.”

I watched my uncle take the heavy gold necklace with its opal pendant from my mother’s neck. My mother lifted up her hands and he began to pull off the rings. She had a small lapis lazuli ring from her childhood, the only piece of jewelry they hadn’t sold during the war. Although it had been stretched, all of her adulthood it had fit snug on her right pinkie. Now it was so loose that it came off without any effort. One finger at a time, the rings were removed, including the gold band and diamond she always wore. My uncle stood up, handed them to me, grabbed me by my shoulders, and sobbed against my shirt.

My father looked up from his chair. “Shlomo, you’ve been a good brother. You don’t have to cry.”

I looked at my mother. She had closed her eyes when she lifted up her hands for her brother. That physical act had required one last push, one last use of the mental will and emotional strength for which she was admired and held in awe. She would never open her eyes again.

CHAPTER 4

From A Lifetime in Mathematics by Rachela Karnokovitch: The Bear

I remember a good deal about our trip to Vorkuta. It was in 1940, in April, I believe, about the time of my tenth birthday. No one celebrated such things in my part of Poland, even in well-to-do homes like ours. It would have been considered decadent and indulgent to bestow such attention on a child. It was a time of war as well.

We had been living in Odessa. My father, ever resourceful, had in advance of the war obtained a letter offering him a place to live, should he need it, from a Karlin-Stolin sect rabbi in Belarus. He presented this letter to a Soviet officer in Vladimir-Volynski, and I don’t know why—no one was being allowed to leave, even those who tried to bribe officials—he stamped our papers. Even the guards looked surprised as they inspected our documents at the Belarus border.

The Mathematician’s Shiva

The Mathematician’s Shiva