- Home

- Stuart Rojstaczer

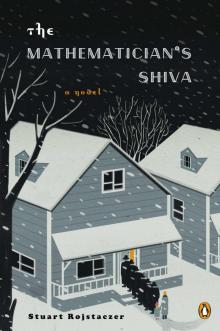

The Mathematician’s Shiva Page 22

The Mathematician’s Shiva Read online

Page 22

My mother decided that my uncle needed a change of scenery, bought him a ticket, and put him on a plane. I picked him up at the Birmingham Airport. My mother wasn’t sure exactly what this move would accomplish, and I wasn’t either. She had no idea what I should do to pull my uncle out of his depression, but I was given one hard rule. “Do not leave him alone.”

I took this command literally. When I went shopping, he went shopping. When I went to work, he went with me. In most workplaces, even academic ones, I’m sure my uncle would not have been welcome. But the South is different, and I was a highly respected member of my community. My uncle was family, and as far as the people around me were concerned, that meant he needed care. The solicitousness over this man so obviously grieving shown by my department staff, a couple of my atmospheric sciences colleagues, a handful of members of the math department—my uncle was the brother of Rachela Karnokovitch, after all—and by the lone Slavic languages professor in my university was touching.

I had an anteroom leading to my office that was full of computer workstations. We moved two of these workstations into the offices of my students. In hindsight, I should have done this years earlier. It turned out the students loved and used those toys even more when they were in close proximity. We set up my uncle as a de facto academic. He read Polish books from the university library while he drank tea and made the transition back from a full-time alcoholic into one who, like me, drinks himself into oblivion only occasionally, after hours.

Three weeks into his visit, a hurricane began to develop in the Gulf. I got a call that I could get some time on a military aircraft at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa to make measurements. I told them I needed to bring along an assistant, a responsible, mature graduate student. Space limitations on the small jet usually meant such requests were denied. I was relieved when they said yes. I brought my uncle along, told him to pretend that he was a student, and showed him how to deploy my instruments.

Something about the idea of flying into a hurricane excited him. It was the first time I had seen anything other than fatigue and grief on his olive-skinned face in more than a year. “It’s dangerous, yes?” He kept asking me, and I kept telling him no.

“The plane is not going to shake and rattle?”

“Not really.”

“Not even a little?”

“Well, a little.”

“Good. How else would you know you’re in a hurricane?” My uncle called my mother, called Bruce, and told everyone on campus that his nephew was going to fly him into a hurricane to make measurements. We flew down to Tampa, rented a car, and on the way to MacDill I told him that he should relieve himself before we went on the plane.

“You think I’m going to shit in my pants flying into this thing? I’m not that kind of man.”

“No, I don’t think so. But there is no bathroom once we’re up in the air. It’s a military jet. No stewardesses. No bathroom.”

“And what if you have to go?”

“There’s a plastic bag.”

“This you didn’t tell me. The most powerful country in the world and its military shits in plastic bags?”

“That’s why I’m telling you now.”

“Thank you. I’m not going to shit in a plastic bag. No way. You ever do that?”

“A couple of times.”

“A Ph.D. big-shot professor. A mother who is a genius. And you shit in plastic bags. Unbelievable.”

On the airplane, my uncle assumed the role of eager graduate student to such a degree that I began to wonder why I had come along at all. We brought four dozen sensors with us that were designed to be placed into the growing tropical disturbance and monitor temperature, wind speed, humidity, and vapor pressure every tenth of a second as they descended from the plane into the ocean below. These sensors, whose measurements were transmitted via battery-operated telemetry back to the plane, were placed in cylindrical tubes about twelve inches long and two inches in diameter. Before we took off, I told my uncle where I wanted the sensors deployed in the storm. He took to these instructions like they were military orders and he was on a vital mission to save our country.

He talked to the pilot to get information on the location of the plane and, when the time was right, would carefully place each tube into the release chamber and then press the eject button. My uncle, I understood then and there, would have made an excellent engineer.

A reporter from the Washington Post was on the plane as well and asked me about my uncle. “Is he a colleague?”

“Oh, yes. From the University of Warsaw,” I deadpanned, and gave the reporter my uncle’s name with the added title of professor. I was half hoping and half dreading that my uncle would be mentioned in the journalist’s story, and that he would receive a professorship via print. Alas, it didn’t happen. But I did put my uncle’s name on the research paper that resulted from the data we collected. One year after his efforts at being a research assistant, I handed him a copy of the article. “Look, I’m a scientist now. It’s not so hard a profession after all,” he said.

That six-hour flight in and out of what would become Hurricane Frieda was the beginning of my uncle’s recovery. You could see it in his step, just the way he carried himself. Sixteen days later he was back in Madison, Wisconsin, running his business again.

The death of his big sister and the certain dissolution of his marriage—Cynthia had flown to Dallas the previous morning—seemed to have put my uncle into another funk. Bruce, Anna, and I sat in the dining room trying our best to keep him from descending any further into despair, while my father, daughter, and granddaughter sat with the mathematicians.

“I feel like the last Mohican,” he said.

“You still have us,” Bruce said.

“It’s true. You three. The young ones. But none of you speak anything resembling a decent Polish. And I’ve never liked living alone.”

“Well, I’m not moving back, Father. It’s too fucking cold here.” Bruce was aiming for forcefulness.

“Yeah, it’s cold. Maybe I should move to Los Angeles. Sell my business. Get the hell out of here.”

“You should sell the house, that’s for sure. It’s depressing. A monstrosity,” Anna said.

“I should set it on fire!” My uncle’s eyes opened wide, as if he had come upon a novel idea.

“You can’t mean that, Father.”

“You don’t think I could?”

“It’s not that we don’t think you could,” I said. “It’s that we think you shouldn’t.”

“I don’t have luck. I thought I was lucky. But no, not really. I have Yiddishe mazel. It clings to me. I can’t shake it. I should have died in that fucking grave in Ukraine. I would have been better off.”

“You should come to Tuscaloosa after this,” I said. “You need some warm weather.”

“You’ll put me in an airplane again? Fly me in a hurricane?”

“In summer, sure. We’ll fly into a hurricane.” I didn’t think this was a bad idea. I could always use quality help.

“And I’ll have to shit into a plastic bag if I need to go. No way. That’s worse than living in Poland.”

“Rachela wouldn’t tolerate you like this,” Anna said. “Feeling sorry for yourself. I don’t like it, either. It’s like you’re a little girl.” Anna was chiding my uncle in earnest. Few had the temerity to do this.

“I’m not a little girl. I just miss my sister. I miss her voice. I wish I could talk to her again. Maybe just one more time, so I could tell her a few things I didn’t say when I had the chance. A man can get sad. There’s nothing wrong with it.”

“It’s OK to be sad, sure, but not like this. Not wishing you were dead. Look at you. A successful man with a successful son. People who love you and care about you. You’re not making sense.”

“You think I should be making sense now? Right now?”

&nbs

p; “Yes. Always. There’s no reason not to make sense.”

“And what would make sense right now?”

“I don’t have to tell you. You know what to do. You’re not an idiot.”

My uncle nodded, looking at his hands. “Three years with that Texas woman were like fifty.”

“You were an idiot about that. But for a good reason.” Anna’s voice had softened. She was done reprimanding my uncle.

“She looked good, didn’t she?” my uncle asked, and gave Anna a look. He wasn’t lost in thought anymore.

“Not bad. No real style, though,” Anna said with a touch of pity.

“She never fought. Just kept it in. If she was happy or unhappy, I never knew,” my uncle said.

“You need someone who understands you. What do American women know?”

“You’re right about that. Their blood runs cold. Not like us.” A smile appeared out of nowhere on my uncle’s face.

“It’s why they can’t dance.”

“It’s why they can’t do a lot of things.” My uncle’s dark cloud had disappeared.

Anna smiled back at my uncle. Bruce got up and walked away from the dining room table without saying a word. It took me a few minutes before I realized why Bruce had left. I walked into the kitchen. Bruce was eyeing Pascha warily. “I was scared of that thing when I was a kid. Tried to pick her up once and she almost bit my finger off.”

“You’re not a pet person, it’s true.”

“What were you doing in there so long? Trying to kill the buzz?”

“I’m a little slower than you in social matters, you know.”

“At least you’re not completely clueless. You did get out of there eventually. I’m proud of you.”

“Where do you think it’s going to lead? You’re the one with a sense for this kind of stuff.”

“Well, she’s not going to his house. She hates the look of that place, and then there’s the Cynthia aura. Probably they’ll end up at the Edgewater Hotel by week’s end.”

“Those two ever been together before?”

“You can’t tell? Honestly?”

“No.”

“You’re hopeless. You can’t tell which of these mathematicians have slept with each other either, can you?”

“No. Not at all.”

“Fact one. The aging Soviet hipster with the goatee and the blonde with the 1980s New Wave ’do are sleeping with each other on this trip.” Bruce was in college lecturer mode.

“Zhelezniak and Potter? You’re like the National Enquirer. The triplets? Ben-Zvi?”

“The triplets are too young for this crowd. But Ben-Zvi and the one who likes business suits. That happened sometime somewhere.”

“Ben-Zvi and Steinberg? I don’t want to think about it. The image is not pleasant at all.”

“Ben-Zvi and Anna, too, don’t forget about that one.” Bruce liked to stir the pot when he was back home.

“He actually looked pretty good back then. But everyone knew that wasn’t going to last.”

“Didn’t Aunt Rachela and the shy math hunk share some time?”

“Orlansky and my mom? Just rumors.”

“I never saw them together. But when he walks into this house it’s not like he’s just another dear old colleague.” The knowing smile of his father appeared on my cousin’s face.

“How can you tell about all these dalliances, anyhow?”

“Body language. The way they look at each other. It’s obvious.”

“So you can tell which of these women I’ve slept with, I suppose.”

“Yeah, I can. Zero.”

“You’re good. Damn.”

“Yeah, that was a stupid trick question. You can’t tell which of these men I’ve slept with, no doubt.”

“The triplets?” I was taking a wild guess.

“Now that would be fun. But two of them are straight. The answer is zero. At least, so far.”

“I can’t tell those three apart and you’ve figured out which holes each of them like to invade.”

“That’s why you’re a scientist and I’m not. Jane has her eyes all over you, in case you haven’t noticed. She’s not bad.” Bruce moved his right hand to a height that indicated his rating of Jane.

“No way am I going in that direction. She’s the heir apparent to my mother, the new queen of female mathematicians. When she stepped into my mother’s skis she acted like she was Cinderella being fitted for her glass slipper.”

“You could be her Prince Charming.” I knew Bruce was teasing me.

“She just wants me for my yikhes.”

“I think she wants more than your yikhes, the way she’s checking you out.”

“Looking is for free. I’m flattered, but not interested.”

“Ari has a certain allure, actually. I’m sure he gets bored being around his brothers all the time. Wants something new now and then.”

“Which one is Ari? They look alike. They dress alike.”

“Ari is the gay one. Anyone can spot the queer in the crowd, right?”

I moved toward the living room and looked at the mathematicians. The triplets weren’t smiling. It was hopeless. “You should stay away from mathematicians, though.”

“I don’t want to live with him. I just want to fuck him. Look, it worked out for you in the end. You might have a tiny math genius to show for it.”

“In a way, you’re right, I guess. I’m still trying to understand my good fortune.”

“Amy looks just like Aunt Rachela. Like a Mini-Me. That’s amazing.” My cousin was actually kvelling.

“It’s not amazing. It’s just boring genetics. But your point is well taken.”

“What are you two gossiping about?” Yakov asked, walking into the kitchen.

“Love,” I said.

“Lust,” Bruce said.

“I don’t want to talk about either,” Yakov said.

“What happened to you and Jenny Rivkin?” I asked.

“Lyubov’ zla, polyubish i kozla.” Yakov spoke as if he had grown used to failing at love.

“Got turned down, did you?”

“Without hesitation. And now look, no food from her either. I’ve scared her away completely.”

“You and Jenny Rivkin? Really? That’s funny. I went to Hebrew school with her,” Bruce said.

“I don’t want to talk about it. I’m going to the zoo. Take a look at the bears. I need some inspiration.”

“How is the Navier-Stokes problem coming along?”

“As bad as my effort at charming Jenny Rivkin. Zhelezniak and Potter, last night both of them went out skiing, hoping the cold weather and the snow would help them understand something, anything. They plan to go out again tonight.”

“They don’t look like they’re getting much sleep after their ski trips,” Bruce said.

“That too.” Yakov smiled. “Comforting each other after the daily defeat. We’re getting desperate.”

“I would think that crashing someone’s shiva would be desperation enough,” I said.

“You’d never know your mother and father and your ex-wife were mathematicians, Sasha.” With that, Yakov, dressed only in a sport coat, polo shirt, jeans, and sockless loafers, went into the cold to search for the bears of the zoo.

CHAPTER 26

A Meeting of the Minds

DAY 4

For the first three nights of the shiva, Bruce, Anna, and I spent quiet time together. At dinner we would eat the food brought by the Sisterhood every day, the strange mix of Jewish, Russian, sixties-style American casseroles, and ostensibly healthy tofu-laden salads. There it was, the culinary result of one hundred years of immigration, education, peer pressure, nostalgia, and, for most, modest to impressive prosperity. After we would be like well-behaved children and read aloud scenes

from a contemporary Russian play translated into English—how and why my mother had obtained the copies was unknown—each of us portraying three different characters so we could cover all the parts.

It had been a sweet time, nostalgic, and it reminded me why, or at least it gave me an initial excuse as to why, I had lived these many years without having anything close to a longtime partner. I already had enough attachments. I was filled up emotionally, or so I thought. There is only a finite amount of love I can give, was my conviction. Between Anna, Bruce, my mother, my uncle, and even my father, how much of my heart was still available? Two new people had instantly entered my family. What room in my heart was there for them, especially given that I was grieving over the loss of the most important person in my life?

This kind of thinking is, of course, stupid, and not even a good use of arithmetic. Our capacity for love isn’t like a gallon jug that you fill up from rest stop to rest stop as you take a drive across the country. It can swell, and sadly, it can shrink. Less is not more. Less is less, and more is better, although I can’t say that I fully understood this at the time of my mother’s death. I’m a whiz at science and math. In matters of people, I am indeed a slow learner.

During the shiva, whatever efforts I would make at finding time to spend with my daughter and granddaughter alone were constantly thwarted by my father, who housed and fed my progeny. But the truth was also that I was a bit scared to meet them without the buffer of others.

I had gone to my father’s house to see my daughter and granddaughter twice. These meetings seemed to me to be artificially sweet, certainly nothing like real time spent with real family. My father didn’t help. Sometimes his smile was true, but I also detected a fair amount of forced conviviality. He seemed to me to be less like a grandfather and more like an upscale department store greeter giving directions. Whenever I tried to have a real conversation with my daughter, my father, either on purpose or out of the cluelessness that comes from pure selfishness, would interrupt or try to enforce a light mood.

The Mathematician’s Shiva

The Mathematician’s Shiva