- Home

- Stuart Rojstaczer

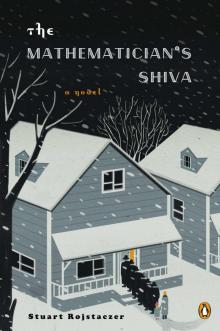

The Mathematician’s Shiva Page 20

The Mathematician’s Shiva Read online

Page 20

Kelly quickly got up off her folding chair.

“All those numbers are from when I was five, when we moved here, until when I was fifteen. My mother always made sure painters never covered this part of the doorjamb. She said she liked to look at it and remember those times, that they were years that she thought of fondly.”

“That’s very sweet, actually.”

“I think so, too. I probably should have covered this up for the shiva, when I think about it. At any rate, we’re going to make a new mark right now. We’re going to bring things up to date. Could you grab a book and a pencil?”

“What are you doing, Sasha? This is crazy,” Eva said.

“Just give Kelly a book and pencil and I’ll show you, Eva.”

Eva pulled a book of Kandinsky artwork from the coffee table and grabbed a nearby pencil, a tool that, unlike wrenches and screwdrivers, was always in ample supply in our house.

“I think you’re tall enough, Kelly. You’ll just have to reach. Put the book on top of my head, make it level, and make a mark.”

I stood erect while Ms. Hickson carefully and accurately took my height. I then turned around and faced the doorjamb. “That was fun, actually, brought back memories,” I said. “Back then I wanted to be taller desperately. My mother would say I must have taken after my grandpa Aaron. The pencil marks went higher every year, but the incremental increases were always pitifully small.”

“What happened here?” Kelly asked, pointing to a big gap

“I went away to school in Chicago. I came back nine months later. I was a foot taller. Pretty much at the height of the mark you made. I was finally taller than my mother, much taller. It made me happy. It made my mother happy, too. But I was never as smart as her. That would never happen. And all of us, smart as we are, are just down here.” I pointed to my height at fifteen, before my growth spurt. “See the gap? That’s the gap between our collective intelligence and my mother’s. Not even close.”

Kelly broke the short silence. “You’re right, Sasha,” Kelly said. “I’ve looked at some of her work. It’s intimidating, but I try to make it inspire me, not depress me.”

“It’s good you know that, Kelly,” I said. “Most people in this room cannot admit it. That was the point of this exercise. I underestimated you. I’m sorry.”

“That’s all right.”

“You know what? You can all look wherever you want. Here. My mother’s office. Even my mother viewed Navier-Stokes as potentially impossible. Look and see what you can find. It’s not going to help, but it will pass the time.”

“Thank you, Sasha,” one of the triplets said. “But my brothers and I don’t think we need your mother’s help. Not directly. Rather, we should do as your mother would do to solve any problem.”

“And what would she do?” I asked.

“It’s obvious,” he said. The brothers even smiled in unison. I noticed one of them had a chipped front tooth. Finally, I had a distinguishing feature I could use. “It’s cold. There’s snow,” another brother with more or less perfect front teeth continued.

“A ski trip, then?” I asked.

“That’s an excellent idea!” Zhelezniak said.

“What do you think, Peter?” I asked.

“I think if we don’t get out of this house tomorrow we’ll end up killing each other.”

“That could happen,” I said. “Do you ski, Professor Hickson?”

“We would go to Vail when I was a kid, but I’ve never done cross-country.”

“It’s very therapeutic. If you are a true acolyte of my mother, you must learn. Everyone in this room knows how to ski.”

“Well, I run every day.”

“I could have predicted that. But cross-country skiing is different. You’ll see.”

CHAPTER 23

The Ski Trip

DAY 3

My mother and father skied cross-country extensively every winter. It’s something that all of Kolmogorov’s former students living in cold climates did, and few of his students deigned to live below the forty-second parallel. Of course, cross-country skiing is also something that I grew up doing.

According to Kolmogorov, ideas needed to flow and ideas came and flowed most easily when the body was subject to a combination of punishing cold and vigorous exercise. What form of exercise was best for this combination? Kolmogorov believed cross-country skiing was tailor-made for intellectual discovery. The shiva-attending mathematicians were therefore very fortunate that the weather gods had chosen to not only dump snow on Madison, Wisconsin, before they arrived, but also to follow that dumping with the migration of a high-pressure Arctic air mass that had decided, like many Arctic air masses, to stagnate.

It was cold during the shiva. How cold was it? It was so cold that during their daily mile walk from their host’s house to my mother’s home, the Karanskys’ considerable hair, which none of them made any effort to dry when they showered in the morning, froze into icicle-encrusted ringlets. It was so cold that, for the safety of the student body, the chancellor closed all evening classes at the university for two of the shiva days, when the night temperature fell into the minus twenties.

Bitter cold meant, as far as most of these mathematicians were concerned, absolutely ideal conditions for cross-country skiing. At these frigid temperatures, those who still preferred to use waxed skis didn’t have to think about what color wax to use or worry about changing waxes in mid-ski. A thin coating of hard white polar wax and they would be on their way.

The glaciers had been kinder to Wisconsin than to the nearby states of Illinois, Iowa, and Nebraska. They had not leveled the entire landscape to the flatness of a bowling lane. Cross-country skiing in Wisconsin came with some modest challenges, huffing and puffing up inclines and gloriously careening down modest hills. The mathematicians were also blessed with a wonderful venue for skiing a mere mile from my mother’s home, just beyond the zoo and ice rink of Vilas Park. The Arboretum was a twelve-hundred-acre prairie preserve maintained by the university.

Excluding my father, who certainly possessed ski equipment of his own, there were fourteen mathematicians who needed skis. Contrary to my words to Kelly Hickson, there were novices and near novices in the troupe. Those who had been students of my mother had been indoctrinated in the positive value of a good ski on the creativity of the mathematical mind. Then there was Zhelezniak, the other direct descendant of Kolmogorov. Zhelezniak was absolutely gung ho about this mission to extract a little more brain power from the group.

Zhelezniak was so adamant that he made it clear to all that refusing to confront the snow and cold would be the equivalent of treason, or at least an open admission that failure to produce a breakthrough to the solution of the Navier-Stokes problem over the course of the shiva was a possibility. News of the planned trip carried to the mathematics department and beyond. Miraculously, the necessary piles of suitable clothing, shoes, and skis appeared the night before and were deposited in my mother’s storm-windowed front porch. We were good to go.

By saying we, I do of course include myself. I had no interest in solving the Navier-Stokes problem, but I was concerned about the inexperienced members of the group, Ito in particular. Plus, I felt a certain pull to get out of the house, slide on the snow, and move my bones. I thought it might prove to be emotionally beneficial. I was actually hoping for the absence of any ideas in my head whatsoever, mathematical or otherwise.

Bruce watched us bundle up with amusement. He, too, was more than competent on skis, but there was no way on earth that he was going to subject himself to such obvious misery. Instead, he pulled his own skis out of the cobweb-filled garage and instructed Ito on their use in the backyard. I did the same with my mother’s skis and Jane Sempralini, a professor of mathematics from Sydney who had only recently moved to Cambridge, England. “This is an honor, quite truly,” she said as I showed her how to step into my mother’s bind

ings.

“It’s cold for you now, yes?”

“Bitter cold. Already, I can’t feel my nose.”

“We’ll get you a scarf. That will help. You’ve never been skiing at all, not even downhill?”

“Never.”

“It’s like walking in the mud. You lift up your feet to get out of the mud and then you press down and get stuck again.”

“Sounds terrible.”

“But there is the added benefit that you don’t really get stuck. You glide. It’s like ice-skating.”

“Can’t say I’ve ever done that either.”

“Roller-skating?”

“That I have done.”

“Good, because there are similarities there, too. You push a bit down instead of away and instead of rolling, you slide along.”

I watched Bruce instruct Ito and tried not to grimace as I watched Jane try to master the push and glide of cross-country skiing in my mother’s backyard. Zhelezniak, my father, Virginia Potter, who skied in the hills outside of Amherst regularly, Peter Orlansky, and the Karanskys would be one hundred yards out before either of these two managed to go ten feet. I informed Zhelezniak of the need to break into two groups.

“What do you mean? We all go out. We all ski. We all come back. It’s simple.”

“It’s not that simple, Vladimir. It’s freezing. There are people who have never been in weather this cold, much less been on skis.”

“It’s like walking. It’s not difficult. You push. You glide. Any idiot can do this.”

“With practice, yes. But you’re going to want to go five miles, at least.”

“At least, of course.”

“Ito and Jane, they’ll be lucky to make a mile. Ben-Zvi won’t be able to do more than two or three. My father will show you where to go. I’ll stay behind with the rest. I know the route my father will take. We’ll use a shorter path and meet you at the end.”

That’s exactly what we did. Ito and Jane and Ben-Zvi were thankful for a less painful, less arduous option, and I guided them as we crawled along the edge of snow-covered Lake Wingra. The cold air bit into the pores of my skin as we made hard-earned progress, and yielded a sensory memory that I thought I would rather have not elicited ever again. As we continued, though, I changed my mind. This was kind of fun. The ski track we followed was by far the gentlest and, with the near constant view of the lake, was also the prettiest. Our stops, to catch our breath or for the occasional spills into the snow, gave me the time to look north beyond the lake toward the zoo where I spent many hours as a kid. I did wish that we could move faster. It was early in the morning on a workday. The trail, which wasn’t particularly well traveled even during weekends, was, lucky for us, empty. After a while, just to keep my blood circulation going, I began to ski ahead a few hundred yards at a clip, and then retreat to make sure everyone was doing as well as could be expected. I kept reminding them to brush off the snow every time they fell, lest it melt on their pants and chill their thighs or roll down into their boots.

On one of my forays ahead, I ran into an industrious skier going in the opposite direction, her rhythm steady, her breath forming little cloud puffs as she progressed across the flats. I didn’t recognize her at first, but the red hair peeking out from her knit cap gave me a clue. She looked up as she approached and I moved my skis off the track.

“Sasha, what are you doing out here?” Jenny asked.

“I could say the same about you.”

“I come here before work two mornings a week. It clears my head. Your mom taught me that. Are you out here clearing your head?”

“Well, not really. It’s the mathematicians. They are trying to find inspiration in the woods. They’re behind me a bit, getting inspired as we speak, I hope.”

“All of them?”

“Yes and no. My father is leading the experts. I’m in charge of the inexperienced ones.”

“I talked to one of them the other day. Yakov. Is he with them?”

“Oh, no, Yakov is actually quite a good skier. He’s with my father. He’s loving your cooking, by the way.”

“Thanks. I’m just trying to help out. You’re making us work overtime, though. We didn’t know there would be so many people.”

“If truth be known, neither did I.”

“I know it must be hard. Your mother was important to me. It’s good to do something instead of thinking about losing her.”

We parted ways and I watched her shush off toward my little troop of skiing neophytes. We had another half mile to go, and if we timed things right, we wouldn’t have to stand around too long before the experts met up with us. I tried to encourage the group, looking for evidence of the remotest bit of glide in their movements. It wasn’t forthcoming. I stopped them to offer an impromptu lesson. I exaggeratedly lifted up and pushed down on one ski.

“This is where the rhythm for skiing comes from,” I said “The planting of your foot, and then that instant feeling of effortless sliding along the compacted snow, which carries you for a second or two before you feel compelled to step down with your other foot. Back and forth, that’s what it’s about, the impending loss of gliding making you lift one foot and then another.”

“I suppose this is a form of meditation,” Ben-Zvi said without irony.

“That’s about right,” I said. “On a good day, if I concentrate simply on the motion of my feet, I can sometimes forget about everything else for a mile or so before I come back into the real world.”

“I’m going to end up with bruises, I’ve fallen so much,” Jane said.

“The more you practice, the better you get. One more time out here and I bet you hardly fall at all.” I could barely believe the earnest tone in my voice. I must have been channeling my mother. I wasn’t trying to sell snow to the Eskimos, or to the Russians for that matter, but I was certainly trying to sell it to the Aussies, Japanese, and one very skeptical Israeli.

Jane asked if we could spend some time making snowballs, and maybe even a fort. “I used to read about children doing that in books. It sounded like so much fun. Much more fun than skiing, from what I can tell.”

“The snow’s too dry for that, sorry,” I said. “But it does make for excellent angels.”

“I’ll settle for an angel,” Ben-Zvi said. “I’m too exhausted to do much of anything else.”

To see a child make an angel in the snow can be a precious thing. There is something about watching kids, normally so erratically active, change pace and mood to splay out in the snow. But to see a burly, bearded man in Clark Kent glasses plop down, make the earth shake slightly, and imitate so ungracefully what a child of the Midwest knows how to do with ease is something else entirely.

“I may not get up,” Ben-Zvi said. “This feels good.”

“If Zhelezniak catches you like this,” Jane said, “you’ll never hear the end of it.”

“Fuck Zhelezniak. I’m beat. No one brought any hot chocolate, did they? That would have been a good idea. Right here. Right now. And then some snow ambulance to take me back. They have one of those?”

“Probably not, Abraham,” I said. “Unless you have a heart attack or something serious, you’ll have to get back on your own.”

“A heart attack isn’t worth it. Does frostbite count?”

“No, I’m afraid not.”

“You Midwesterners are a tough lot.” He lifted himself from the snow and looked down at the depression. “I didn’t know I could be so angelic.”

“That’s a big angel, Abraham,” Jane said.

“Oh please, Jane.”

“I guess this little trip isn’t producing much inspiration,” I said.

“Can’t say it is,” Jane agreed.

“It’s simply cold,” Ito said.

“I think you have to be born into it,” I said.

“You find it i

nspiring do you, Sasha?” Ito asked.

“Sometimes, yes,” I said.

“But it’s my understanding that you live in the southern part of the United States now,” Ito said.

“Heat can be inspiring, too. Although my mother wouldn’t agree with that sentiment,” I said.

The group of skiing enthusiasts eventually met us on the edge of the lake. I felt a tinge of envy looking at them, ruddy-faced from a good, physically draining workout. I knew how their lungs felt, raw and free from sucking in gulp after gulp of cold, dry air. My imagination was big enough to sense the collective messy rhythms of all their hearts pounding hard and fast, sometimes in unison, but usually at different tempos. For the first time in years I felt an urge to simply take off on my skis and go by myself into the woods for hours on end.

“This crew is beat,” I said to Zhelezniak and my father. “It’s going to take a lot of work to get them back.”

Zhelezniak looked at the three mathematicians I’d moved along the shore. “They’ve hardly done any skiing at all and look at them! How far is it back, Viktor?”

“Two kilometers, perhaps,” my father said.

“Only two kilometers they’ve gone, and they look as if they will die any minute. Unbelievable,” Zhelezniak said. I have no problem with self-righteousness, and think it has a place when it’s an honest expression of the ability to withstand hardship without complaint. If there is one hardship Russians can endure, even celebrate, it’s cold, and the deprivation associated with that cold. Every hundred years or so another country forgets about this special Russian talent, declares war, and pays dearly for their naiveté and hubris.

“Why don’t we cross the lake?” Ben-Zvi asked, hopeful of a shortcut to my mother’s home.

“It’s really not a good idea,” I said. “The lake looks solid, but there are a lot of hidden springs where the ice is thin. You have to know where they are. I don’t remember just where, it’s been so many years. Father, what about you?”

“I haven’t crossed the lake in a long time. It’s usually too windy.”

The Mathematician’s Shiva

The Mathematician’s Shiva